Cow-Calf Profitability Estimates for 2022 and 2023 (Spring Calving Herd)

Author(s): Greg Halich, Kenny Burdine, and Jonathan Shepherd

Published: February 28th, 2023

Shareable PDF

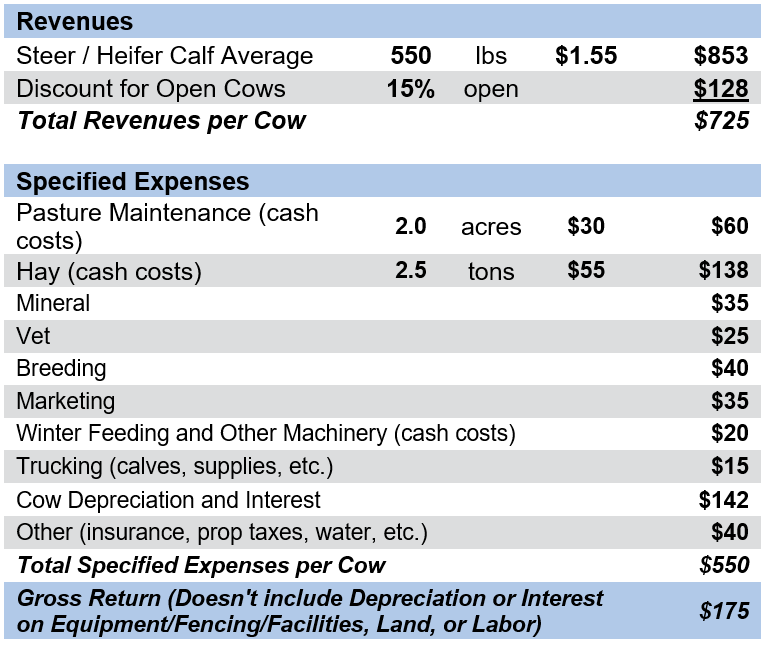

The purpose of this article is to examine cow-calf profitability for a spring calving herd that sold weaned calves in the fall of 2022 and provide an estimate of profitability for the upcoming year, 2023. Table 1 summarizes estimated costs for a well-managed spring-calving cowherd for 2022. Every operation is different, so producers should evaluate and modify these estimates to fit their situation (see Table 2). Note that in Table 1 we are not including depreciation or interest on equipment/fencing/facilities, as well as labor and land costs.

Calves are assumed to be weaned and sold at an average weight of 550 lbs. In the fourth quarter of 2022, steers in this weight range were selling for prices in the upper $160’s and heifers in the low $140’s, on a state average basis. Therefore, a steer / heifer average price of $1.55 per lb is used for the analysis, which was $0.15 per lb higher than last year. Calf prices have increased significantly since that time, but this analysis assumes that spring born calves are sold late in the same year. Weaning rate was estimated at 85%, meaning that it is expected that a calf will be weaned and sold from 85% of the cows that were exposed to the bull. Based on these assumptions and adjusted for the weaning rate, average calf revenue is $725 per cow.

Cost-wise, the major changes for 2022 were significant increases in fertilizer and fuel prices. Nitrogen, potassium, and diesel fuel prices more than doubled between 2021 and 2022. The biggest impact that these had collectively was on hay production costs, but many other areas were impacted as well. However, general price increases were seen in almost all cost categories. These are all reflected in the cost estimates for 2022.

Pasture maintenance costs are assumed to be relatively low at $30 per acre and would include only basic cash costs of pasture clipping (fuel, maintenance, repairs), and a limited amount of reseeding, fertilizer, and fencing repairs. Cattle farmers who consistently apply large amounts of fertilizer to pasture ground would see much higher pasture maintenance costs. The pasture stocking rate is assumed to be 2.0 acres per cow, but this will vary greatly. Stocking rate impacts the number of grazing days and winter feeding days for the operation (i.e. high stocking rates will mean more hay feeding days), which has large implications for costs on a per cow basis.

These spring calving cows were assumed to use 2.5 tons of hay per cow, and the estimated cash cost of making this hay (fuel, maintenance, repairs, supplies, fertilizer, etc.) was $55 per ton. Mineral cost is $35 per cow, veterinary / medicine costs $25, trucking costs $15, machinery cash costs for winter feeding and other miscellaneous jobs is $15, and other costs (insurance, property taxes, water, etc.) are $40. Breeding costs are $40 per cow and should include annual depreciation of the bull and bull maintenance costs, spread across the number of cows he services. Marketing costs are assumed to be $35 per cow (adjusted for the 85% calf crop) for average-sized farms selling in smaller lots. Larger operations would likely market cattle in larger groups and pay lower commission rates.

Breeding stock depreciation and interest are major costs that are often overlooked. They are generally not cash costs that need to be paid on a yearly basis, unless you have a loan on the cattle, but they are real costs that need to be paid at some point. As an example, assume that in a typical year bred heifers are valued at $1600, have eight productive years, and have a cull cow value of $850. The average yearly depreciation is calculated as follows:

$1600 bred heifer value

–$808 cull-cow value (adjusted for a 5% death loss)

$793 total depreciation

$793 depreciation / 8 productive years = $99 cow depreciation per year. The actual depreciation will vary across farms. When buying bred replacement heifers, the initial heifer value is clear. With farm-raised replacements, this cost should be the revenue foregone had the heifer been sold with the other calves, plus all expenses incurred (feed, breeding, pasture rent, etc.) to reach the same reproductive stage as a purchased bred heifer. At an average value of $1225 (halfway between bred heifer and cull value) over her lifespan on your farm, and assuming a 3.5% interest rate results in a $43/cow/year interest cost, or a total of $142/cow/year in combined depreciation and interest.

Note that based on the assumptions in our example, total specified expenses per cow are $550 and revenues per cow are $725. Thus, the estimated gross return is $175 per cow. At first glance, this positive return looks impressive, but is also misleading. A number of costs were intentionally excluded because they vary greatly across operations. Notice that no depreciation or interest on equipment/fencing/facilities was included. Notice also that labor and land costs were also not included. Thus, the gross return needs to be adjusted by these costs to come up with a true return to the farm.

Table 1: Estimated Gross Return to Spring Calving Cow-calf Operation 2022

Since these costs vary so much from one operation to the next, it may be helpful to pick a specific sized farm and provide estimates for these costs: a 40-cow operation that is producing its own hay and has all farming operations on its own land (80 acres of pasture and 30 acres of hay).

Assume this farm has on average $50K in equipment which depreciates roughly $1000 every year, or $25/cow/year in depreciation. At 4% interest, an additional cost of $2000 in interest per year, or $50/cow/year, would be realized. Assume also this farm has fencing, barns, working facilities, etc., with an initial value of $50K and a lifespan of 25 years. That would amount to $50/cow/year in depreciation and $25/cow/year in interest.

If we have 2.0 acres of pasture and .75 acres of hay per cow, and value that at a land rent of $36/acre, that would be $100/cow/year in land rent. Assume also that we have determined we have $100/cow/year in labor, which would amount to $4000 total per year for the entire herd.

Summary of Additional Non-Cash Costs (40-Cow Example Farm):

Equipment Depreciation $25/cow/year

Equipment Interest $50/cow/year

Fencing-Facilities Depreciation $50/cow/year

Fencing-Facilities Interest $25/cow/year

Land Rent $100/cow/year

Labor $100/cow/year

Total Additional Non-Cash Costs $350/cow/year

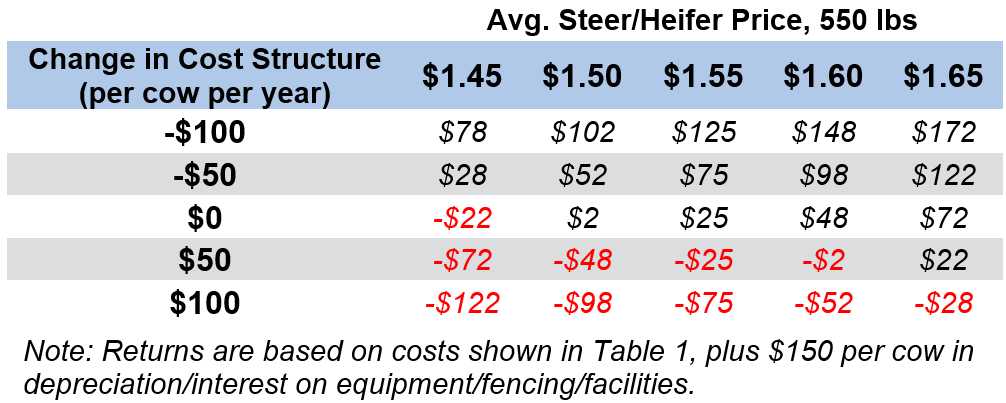

These non-cash costs add up to $350/cow/year on our example farm: $150 per cow in depreciation/interest on equipment/fencing/facilities and $200 per cow in land rent and labor. We encourage you to estimate these for your own operation, but the unfortunate reality is that they quickly add up on most farms. The $175/cow/year gross return over cash costs and cow depreciation does not look quite as good now. After adjusting for these other costs, the net return (all costs included) is –$175 per cow per year ($175 – $350), or –$7000 total for the 40-cow farm.

Another way to look at this is to just include the depreciation and interest for equipment/fencing/facilities ($150/cow/year), and not include land and labor ($200/cow/year). In this case, the return would increase to $25/cow/year and would represent the farms return to land and labor. Did this farm actually lose money on a cash basis? No, not if they are using their own labor and their land is paid for. But the farm also did not make a real profit. This farm essentially paid the equipment/fencing/facilities depreciation and interest in full but only part of the labor-land cost: The farmer and the land worked for free roughly 7/8 of the time.

These numbers will vary across operations, so estimating your own cost structure is extremely important. Our guess is that compared to our example farm, there are far more cow-calf operations of similar size with a higher cost structure than there are operations with a lower cost structure in Kentucky. Put simply, well-managed spring calving herds were likely covering all cash costs, breeding stock depreciation/interest, and depreciation and interest on equipment/fencing/facilities, but were not generating much of a return on their labor or land this last year.

Readers can use Table 2 to modify the analysis based on their cost structure and calf prices for 2022. It uses all costs except for land and labor, so the table shows a return to land and labor using the cost structure in our example. As an example, we used $1.55/lb in our base scenario as the steer/heifer price for 2022. Given the cost structure we used ($0 change on the left hand side of the table), the expected return to land and labor is $25/cow/year, just as was previously described. If a cattle farmer sold their calves for an average price of $1.55/lb but had a $50/cow/year cheaper cost structure (-$50 change on the left hand side of the table), their expected return to land and management would increase to $75/cow/year. If another cattle farmer sold their calves for an average price of $1.60/lb calf, and had a $50/cow/year cheaper cost structure (-$50 on the left hand side), their expected return to land and management would increase to $98/cow/year. In this last example, they fully covered their depreciation/interest on all equipment and facilities, fully covered their land rent, but worked for free.

Table 2: Estimated Return to Land and Labor (per cow) to Spring Calving Cow-Calf Operation given Changes in Cost Structure and Calf Prices

Discussion

Even though calf prices were better in 2022 compared to 2021 (+$.15/lb), projected profitability is lower due to increases in cash costs ($94/cow higher in 2022). Again, this was largely driven by significant increases in fertilizer costs, and to a lesser degree, fuel costs. Farms that rely less on commercial fertilizer would have had better profitability than what we show here.

We also assumed an average-sized cattle farm that would sell at the higher commission rate and would likely get a lower sales price for calves compared to larger operations. Larger operations that can sell at the lower commission rate and generally get better calf prices for selling in larger lots would have had better profitability than what we show here.

Finally, one important assumption that we made that would change on some farms relates to culling open cows. Our assumption for an average-sized farm was that they would not pregnancy-check cows in the fall and would thus not cull open cows at that time. Farms that are able to cull open cows in the fall at weaning time and avoid the expense of wintering them would have had better profitability than what we show here. These open cows would be replaced with bred heifers that would incur wintering costs, but would be very likely to produce a calf the following spring.

2023 Outlook

There is good reason to expect higher prices for 2023, and calf prices have already risen quite a bit since last fall. The size of the US cowherd continues to shrink and is 9% smaller than it was in 2019. Additionally, beef exports set a record in 2021 and broke that record again in 2022. While uncertainty exists, 2023 is likely to be the best calf market we have seen since 2015.

Our best guess for fall 2023 prices for that same 550 lb steer/heifer are in the $1.85-1.95/lb range, or $1.90/lb average. Spring prices are likely to be much higher than this, but we do expect calf prices to decline seasonally by fall. Reducing the costs slightly for fertilizer for hay/pasture and fuel, but increasing marketing costs and the amount of hay fed in 2023 (due to drought conditions during the 2022 growing season), results in a return to land and labor of $198/cow/year. Recall that in our example we had estimated $200 per cow in land rent and labor. Thus we would essentially fully cover our land and labor costs in 2023 in our example farm, which would be a considerable improvement over 2022.

Fertilizer prices have come down in 2023 compared to the unprecedented high levels in 2022. However, they are still roughly 50% higher than pre-2022 levels. In this analysis, we assumed a below-average fertilizer dependency to sustain a beef cow unit. Farms that use higher levels of fertilizer will have lower profits than we show here. Thus managing around these high fertilizer prices is still of paramount importance. For practical strategies to reduce or eliminate fertilizer use on cattle farms see the February 2023 video “Strategies to Reduce Fertilizer Use on Cattle Farms.”

The article “Reducing Your Dependency on Commercial Fertilizers - Strategies for Cattle Farms in 2022 and Beyond” is also available to read.

Market fundamentals suggest that calf prices should be at very high levels in 2023 and the same should largely hold in 2024. Still, calf prices are only part of the story, and we hope this article highlights the importance of cost control. Ideally, costs for a given operation would be structured such that attractive profits can be had at these high calf prices. However, there will be farms that will still struggle to cover all their costs, even with the higher calf revenues.

Many farms will be tempted to increase the size of their cow herds in response to these high calf prices. However, two cautionary red flags should be waved at this point: 1) During the last time of extremely high calf prices (2014-2015), bred heifer prices got bid up to the point where they would only pencil out with continued high calf prices. Those calf prices collapsed quickly leaving those that expanded with low revenues to support paying for those high-priced breeding stock. 2) Concentrating on high-priced calves and ways to produce more of them takes away focus from reducing costs that are out of control on many farms. If you are not generating a true profit (above what would give you and your land a fair return) in the current market, you are almost certain to be in the red when calf prices come back down to more normal levels. Most farms would be better served to concentrate on reducing their cost structure to better position themselves for the lean times that are almost sure to follow.

Greg Halich is an Associate Extension Professor in Farm Management Economics for both cattle and grain production and can be reached at Greg.Halich@uky.edu or 859-257-8841. Kenny Burdine is an Extension Professor in Livestock Marketing and Management and can be reached at kburdine@uky.edu or 859-257-7273. Jonathan Shepherd is an Extension Specialist in Farm Management and can be reached at jdshepherd@uky.edu or (859) 218-4395.

Recommended Citation Format:

Halich, G., K. Burdine, and J. Shepherd. "Cow-Calf Profitability Estimates for 2022 and 2023 (Spring Calving Herd)." Economic and Policy Update (23):2, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Kentucky, February 28th, 2023.

Author(s) Contact Information:

Greg Halich | Associate Extension Professor | greg.halich@uky.edu

Kenny Burdine | Associate Extension Professor | kburdine@uky.edu

Jonathan Shepherd | Extension Specialist | jdshepherd@uky.edu

Recent Extension Articles

Valentine’s Day: One of a Flower Grower’s Favorite Holidays

Savannah Columbia | February 28th, 2023

Valentine’s Day has topped its historical spending record for the second year in a row. Popular gift items include candy or chocolate, flowers, greeting cards, jewelry, and/or dinner reservations. Experience gifts are making an impact in the local food and business scene, as local producers offer various “experiences” to consumers. For Valentine’s Day, many cut flower growers offered the gift of a bouquet subscription that could be purchased for someone.

U.S. Beef Cow Herd at Lowest Level Since 1962

Kenny Burdine | February 2nd, 2023

USDA-NASS released their January 1, 2023, cattle inventory estimates on the afternoon of January 31st. There was really no question that the beef cattle herd had gotten smaller; it was really just a question of how much smaller it had gotten. A combination of dry weather, higher input costs, and strong cull cow prices resulted in an 11% increase in beef cow slaughter during 2022.