U.S. Ag Trade Deficit Continues to Widen

U.S. Ag Trade Deficit Continues to Widen

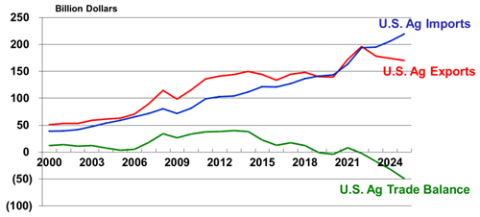

The balance of trade, measured by the difference in a country’s value of exports versus the value of its imports, has received a lot of attention in recent months. While the overall U.S. economy has experienced negative annual trade balances for decades, U.S agriculture has historically recorded annual trade surpluses. Prior to 2019, the last time U.S. agriculture observed a trade deficit was in the 1950s. However, this situation has reversed in recent years as U.S. agriculture has become a net importer.

U.S. agricultural exports have been slumping the past couple of years in response to a relatively strong U.S. dollar, competition from South American crops, lower commodity prices, and a slowing global economy. According to USDA’s latest Outlook for U.S. Agricultural Trade (February 2025) report, U.S. ag exports are projected to total $170.5 billion in fiscal year (FY) 2025, down 13% since its record level of $196.1 billion in FY 2022. On the other side of the ledger, U.S. agricultural imports are forecast to continue to increase to record levels of $219.5 billion in FY 2025, up 13% since FY 2022. Consequently, the U.S. agricultural trade balance is estimated to swell to a record high level of $49 billion in FY 2025 – the fifth year of recording a trade deficit in the past seven years.

Figure 1. U.S. Ag Trade Balance by Fiscal Year

Source: ERS/USDA

Mexico, Canada, China, and the European Union (EU) are the largest exports markets for U.S. agriculture, but these are also the same markets that are currently in a major trade debate with the U.S. Despite the economic importance of these four export markets for U.S. agriculture, the U.S. faces significant ag trade deficits with each of these markets, with the EU exporting $22 billion more in ag products to the U.S. in 2024 than it purchased from the U.S., Mexico registering a $18.3 billion ag trade surplus with the U.S. and Canada with a $12.6 billion ag trade surplus with the U.S.

The U.S has traditionally been a net importer of fruits and vegetables, primarily due to Americans demanding year-round availability of these food products plus labor cost advantages for these labor-intensive crops, primarily coming in from Mexico and Central/South America. Demand for these horticultural crops has intensified in recent years as Americans attempt to improve their diets by consuming more fresh fruits and vegetables. In addition, the U.S. continues to purchase an increasing volume of food and drink products from Mexico, Canada, and Europe, along with imported lean beef from markets like Australia and New Zealand to blend with fattier U.S. raised beef for ground beef production. Of course, there are ag products that are imported simply because the United States is not a major producer such as is the case with coffees, teas, avocados and certain fertilizers. In recent years increasing imported vegetable oils (used for a variety of uses including foods, plastics, and biofuels) and alcoholic beverages (distilled spirits, wine, and beer) have contributed to rapidly rising imports and boosting the overall U.S. ag trade deficit. Within Kentucky, imported tobacco has played a huge role in the demise of the Kentucky tobacco growing sector.

Tariffs become a policy tool to address trade deficits, with the goal of raising revenues and boosting domestic consumption of U.S. produced goods. However, the net effects of a particular industry following tariff adoption depends on the retaliatory action by our foreign competitors and the ability to displace imports and lost exports with additional domestic demand. In general, U.S. ag faces higher tariffs and trade restrictions in many important export markets than foreign producers face with similar products imported into the United States. Consequently, the Trump administration is promising reciprocal tariff action in the coming weeks to “level” the playing field in the international marketplace which could cause additional reaction by our trading partners.

Overall tariffs/trade wars generally hurt export-dependent industries like U.S. agriculture as reduced export demand leads to lower export volumes, puts downward pressure on farm-level prices and tends to inflate input prices for imported items like fertilizer and farm equipment/parts coming into the United States.[i] A recent USDA study (The Economic Impacts of Retaliatory Tariffs on U.S. Agriculture), concluded that the 2018-2019 trade war led to $27 billion of U.S. agricultural export losses due to retaliatory tariffs invoked by U.S. trade competitors. In response to trade losses, the Trump administration provided $23 billion in trade assistance called Market Facilitation Payments (MFP). Farm groups and certain members of Congress are currently lobbying for similar trade assistance programs to become available if a lingering trade war evolves. This outcome, along with the trade policy direction and trade volume impacts remain very uncertain amidst a current vulnerable and depressed U.S. farm economy.

[i] See Gardner G., 2025. Tariffs and Trade: The Cost to US. (Kentucky Field Crops News, Vol 1, Issue 3. University of Kentucky, March 14, 2025 ) for discussion on the effects of tariffs on U.S./KY grains.

Recommended Citation Format:

Snell, W. “U.S. Ag Trade Deficit Continues to Widen." Economic and Policy Update (25):3, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Kentucky, March 31, 2025.

Author(s) Contact Information: